Types of UTI and how they are treated

Read more about different types of UTIs that may affect people with dementia and how treatment differs for each one.

- Urinary tract infections and dementia

- What can cause a urinary tract infection?

- You are here: Types of UTI and how they are treated

- Obtaining samples of urine to test for a UTI

- UTIs and delirium

- Tips to prevent UTIs in people with dementia

- UTIs and dementia - useful organisations

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) and dementia

How are different UTIs treated?

The urinary tract

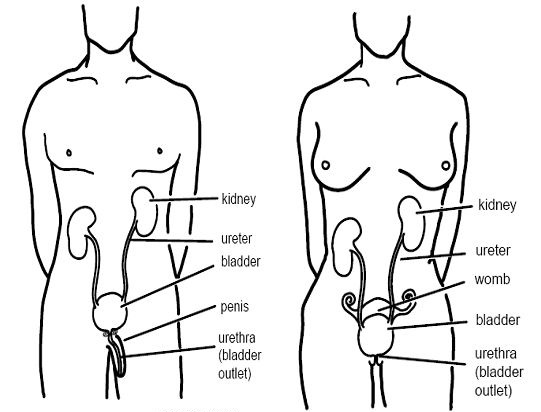

This diagram shows the urinary tract in men and women.

The urinary tract is made up of two kidneys and their ureters (tubes linking the kidneys with the bladder), the bladder and the urethra. The kidneys are bean-shaped organs that filter waste products from the blood and convert them into urine. The ureters are hollow tubes that transport urine from the kidneys to the bladder. The bladder is a muscular sac that has two functions: to store urine and to pass urine from the body. The urethra is the tube from the bladder that allows the passing of urine. It is much shorter in women than in men.

Lower urinary tract infection

This is when only the urethra and/or bladder is infected. A diagnosis of lower urinary tract infection can be made using a simple urine dip test.

The symptoms of a lower urinary tract infection include at least one of the following:

- pain, or a burning sensation when passing urine (called dysuria)

- the need to pass urine immediately (called urgency)

- the feeling of not being able to urinate fully

- cloudy, bloody or bad-smelling urine

- lower abdominal pain

- urinary incontinence – the involuntary leakage of urine

- mild fever (a high temperature between 37–38°C or 98.6–101.0°F)

- delirium/acute confusion (sudden onset confusion developing within one to two days) – this is more common in the elderly.

Treatment of lower UTIs

Lower UTIs are usually treated with a three-day course of antibiotic drugs. Over-the-counter pain relief, such as paracetamol, may also be taken to relieve any associated discomfort.

A urine sample should be taken and sent to a laboratory to identify which bacteria are present. This is called a urine culture. A doctor may request a urine culture for a number of reasons:

- if a person has had two or more UTIs in the past three months

- if there are traces of either blood, white blood cells (immune cells produced in response to infection) or nitrites (a substance produced by bacteria) in the urine when the dip test is performed

- if a person has any abnormalities of the urinary tract (for example, problems with bladder function).

Lower UTIs in men may require further investigation by a urologist. This might include blood tests, an ultrasound scan of the kidneys and bladder, a rectal examination to assess the prostate gland or a cystoscopy to look inside the lower urinary tract with a camera. In some cases the underlying cause may be prostate disease or other urological conditions, such as a bladder stone or tumour, that prevent complete emptying of the bladder.

Upper urinary tract infections

This is when the kidneys and ureters are infected, often in addition to the urethra and/or bladder. It is a more serious condition than a lower UTI as it can result in kidney damage if not treated. Upper UTIs can be accompanied by bacteria in the blood (bacteraemia), and can be life-threatening if left untreated.

The symptoms of an upper UTI may include those of a lower UTI (see above), as well as:

- high fever (a high temperature over 38°C or 101.0°F)

- nausea or vomiting

- rigors (shaking or chills)

- loin pain (may only be on one side)

- flank tenderness (on the side of the body between the ribs and hip).

Treatment of upper UTIs

Treatment for people with upper UTIs usually includes a 7- or 14-day course of antibiotic drugs. For serious upper UTIs, people will need to go to a hospital for further testing and antibiotics that are given intravenously (directly into the veins, via a needle attached to a drip). Men are usually referred to a urologist for investigations if they have symptoms of an upper UTI.

Catheter-related UTIs

Urinary catheters that stay in the bladder (known as ‘indwelling’ catheters) are a major cause of UTIs and should be avoided wherever possible. Even with the most careful hygiene, people using an indwelling catheter are very likely to develop bacteria in the urine at some point.

Intermittent catheterisation, where a catheter is inserted to drain the urine once or several times a day and then removed, carries less risk of infection. However, repeated catheterisation is likely to be extremely distressing for people with dementia who are unaware or have difficulty understanding the procedure, so must be avoided where possible.

It may be necessary for a person to use an indwelling urinary catheter after surgery, for example, but the catheter should be removed as soon as possible so the person can regain their usual bladder function. This will minimise the risk of infection. The longer an indwelling catheter is in place, the higher the risk of infection.

Treatment of catheter UTIs

If people using a catheter have a fever, associated loin (kidney) or bladder (suprapubic) pain, or other symptoms of a UTI, then a urine sample ought to be sent to the laboratory for a test to determine the type of bacteria involved. These people may be started on a course of antibiotics immediately, depending on the severity of the symptoms.

Recurrent UTIs

If a person has more than two episodes of urinary tract infection in three months, this is described as recurrent.

Treatment of recurrent UTIs

Referral to a urologist for further investigations is recommended. Sometimes recurrent urinary tract infections are managed with low-dose, long-term antibiotics.