Real stories

‘You need time to reset’: How I cope caring for my husband with dementia

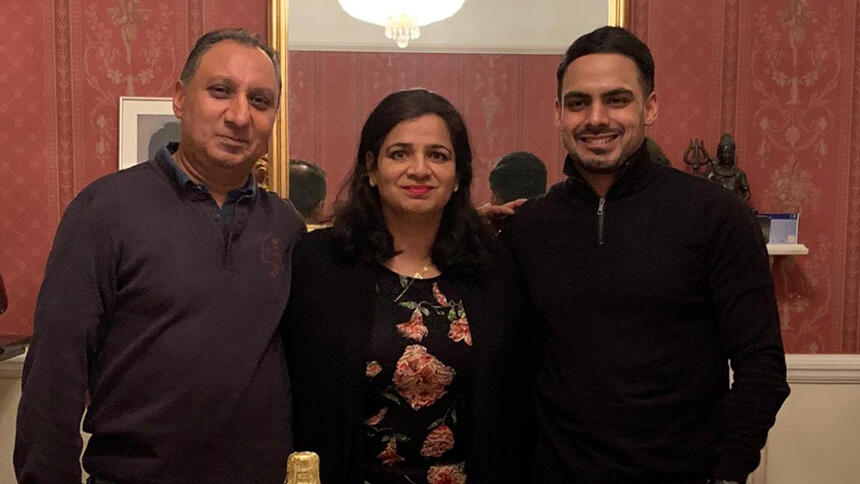

Amar, in Hertfordshire, says caring for her husband Parminder has been a steep learning curve.

‘Every evening I get in the bath with my Kindle, lock the door and stay there for an hour.’

It might not sound like much, yet this simple act of self-care is one of the things that keeps 57-year-old Amar Sunda going.

Through the daily challenges of caring for someone with dementia, Amar hasn’t always prioritised herself.

It has been seven years since her 59-year-old husband Parminder was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia.

She recently took up exercise to boost her health and wellbeing, and she’s already seeing the benefits.

‘Caring is very difficult and you need to take time to reset,’ she says. ‘I do yoga, which I find calming, and recently I went on holiday for five days, leaving my children and the carer in charge, and came back like a new woman.’

Married life was busy for Amar and Parminder

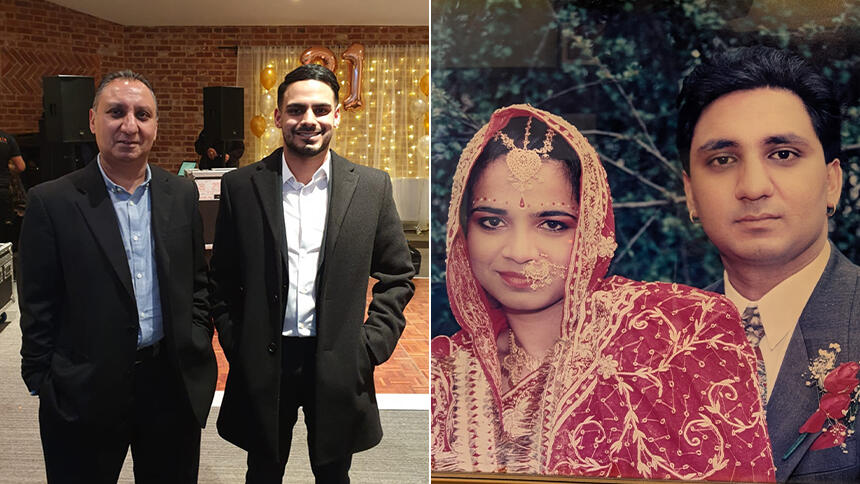

Amar and Parminder’s story began with an arranged Sikh wedding 35 years ago, and later a son and daughter.

Right from the start, Birmingham-born Amar paid her own way. One of six daughters, she says her dad wanted them all to be educated.

‘After school I studied for a legal secretarial diploma. Then it was straight into work at a law firm in Birmingham, and then a London firm for 27 years.’

Parminder spent 28 years with the Department of Trade and Industry, travelling the world to promote British companies.

Noticing behaviour changes

After Parminder took voluntary redundancy in 2015, Amar started noticing concerning behaviour.

‘Someone we knew had an Indian restaurant and he approached them to go into partnership.

‘I asked, “Why are you doing this? This is something we don’t know anything about.”

But he wouldn’t listen, and a couple of months later the business had to be sold and we lost the money.

Showing signs of memory loss

After picking up a few driving jobs, in 2017 Parminder started working as a postman. But a year later, Amar was alarmed when he started to forget the names of people they’d known for 30 years.

‘I said, “You need to speak to a doctor.” But the GP said there was nothing to worry about and that it was just something that happens when you get older.’

That didn’t seem right to Amar.

She started a job in finance the following year, which had medical insurance, so she took him to a private GP for a second opinion.

Getting a dementia diagnosis

‘The doctor carried out tests, and when we went for the results, he said, “I’m no expert but I think this is a cognitive matter,” and said Parminder should be referred for more investigations, including a spinal tap and an MRI scan.

‘After the second appointment, the hospital rang me and said it was conclusive that he had frontotemporal dementia, semantic variant.

‘I thought, “Oh my God,” and had a little cry in the kitchen. I didn’t know anything about dementia, but I went into “mummy mode”.

‘I thought, “We can fix it, and as long as it doesn’t get worse, we can manage this.”

‘I tried to talk to Parminder about it, but he said, “They don’t know what they’re talking about. They’ve got it all wrong.”’

Driving and dementia

Parminder has struggled to accept the diagnosis, which is challenging for the family.

‘He sees dementia as like having a headache and is always looking for a quick cure – a golden tablet,’ says Amar.

This belief in a cure led Parminder to jump in the car and head for A&E and his GP’s surgery as often as once a week. He would drive to Leicester and back in one day to drop in on relatives.

But the DVLA ended up revoking his licence, and Amar was forced to sell her beloved car. She now uses her daughter’s, which Parminder accepts he can’t drive.

Working with dementia

In 2020, Parminder was still working as a postal worker but kept coming home early and was off work for a while, without explaining why.

Eventually, Amar called his union rep and told them that Parminder had dementia.

‘He said he already knew, they had referred him to an occupational therapist and were thinking of ways they could support him.’

Although his work were good at making adjustments, including to his schedule, it soon reached a point where this was no longer possible.

‘It wasn’t long before they called to say he had become agitated at work and had become aggressive.

‘The union rep said he couldn’t see a way back from that, and he was laid off in December 2022.’

Caring and having a full-time job

Losing Parminder’s income was a major worry, but an Alzheimer’s Society dementia adviser helped them apply for PIP (Personal independence payment) and secure a Blue Badge for parking.

An Admiral Nurse signposted them to support too, and a carer’s assessment with the local authority resulted in funding for 10 hours of respite care a week.

As Amar is still working full-time, she has had to self-fund a further 40 hours of care a week, but she says it’s money well spent.

‘We are lucky the carer is a friend and someone we can trust, and who Parminder feels comfortable with. I don’t have to worry about leaving him to go to the office.’

Amar says her employer has been flexible and understanding.

‘They told me I could work from home as much as I needed to, and don’t mind what hours I do as long as the work is done.’

Now living in Bishop’s Stortford, Amar is also fortunate to have help from their adult children.

‘Our son lives in Birmingham and comes over every other weekend, and our daughter travels from London in the week.’

We’ve got each other and juggle everything between us.

But although Amar has felt supported in many ways, stress has taken its toll on her health. She has put on weight and is medicated for an autoimmune disorder and high cholesterol.

Dealing with dementia stigma

It has been tough for Amar to watch Parminder change from a sociable, sport-loving man who loved to travel.

He now needs rigid routine and has some unusual behaviours like smothering his food – including dessert – in ketchup. But she’s philosophical.

‘Life hasn’t turned out how I hoped it would be, but it is still manageable,’ she says. ‘There are people in worse situations and I am grateful for everything I have.

I have had to develop patience. If I hadn’t, I would have been a lot more stressed.

‘And from knowing nothing about dementia, I have had to become a bit of expert to advocate for him. Because if I didn’t do it who would?’

One of the things that helps Amar stay positive is making a difference to others.

Supporting Alzheimer's Society's work

She’s a member of our Dementia Voice group for people from South Asian communities. Amar hopes to raise dementia awareness among South Asian communities, including by providing dementia information in temples.

‘In India, there is a stigma about dementia. They call it a weakness of the head, and the attitudes stop people from going for help,’ she says.

Amar believes there should be far more knowledge about dementia in the general population too.

‘People hear the word dementia and back off. It’s like cancer 20 years ago.

People thought it was like signing a death warrant but now there is more awareness.

‘I hope the same will happen for dementia. It is part of life and there is going to be a lot more of it.

‘One in three of us will get it. It is not an old person’s disease and I hope one day we won’t be so scared.’