Role reversal: Adapting to the impact of dementia

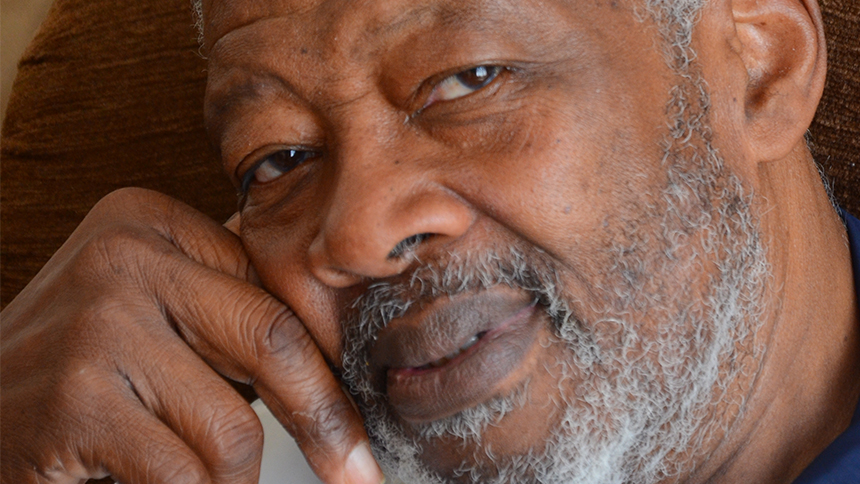

We meet Kenrick Goppy, a man with dementia who is learning to accept that he is now someone in need of support.

‘In many respects, life is rich,’ says an upbeat Kenrick Goppy, sharing insights and anecdotes about his work, family and philosophy.

However, since he developed dementia, Kenrick’s optimistic outlook – although genuine – overlays a real struggle to remain the man he used to be.

Press the orange play button to hear this story in Kenrick's own words:

Family network

Kenrick, 73, grew up in Guyana, a Caribbean nation on the South American mainland.

‘Life there was fairly good,’ he says. ‘If you’re making an English comparison, it was like being middle class.’

Kenrick’s grandmother came from what he describes as an influential family. Her eldest brother, Kenrick’s Uncle Charlie, was a sea captain who is the first African Caribbean person recorded as having skippered a ship through the English Channel.

In his early years, Kenrick spent a lot of time with his aunt and grandmother while his mother was at work.

‘The older generation always wanted to have the grandchildren around them,’ he says. ‘In that respect I was mothered and double mothered!’

Kenrick moved to England in the early 1960s in his mid-teens, joining relatives who were already in London.

‘Those early days were quite exciting – there was a family network,’ he says.

Kenrick was a keen boxer and gymnast, although he had to give these up after starting A-Levels.

‘I was studying and also working to pay my way, meaning there was competition for my time,’ he says.

‘I’d go straight from college to do an evening shift at the post office, go to bed around midnight and get up at 6 or 7 in the morning to get out again.’

Direct approach

He became involved in community youth work, setting up Saturday schools in local churches and teaching boxing and gymnastics.

‘We started to find the failure of young African Caribbean kids, particularly boys, in the school system,’ he says.

‘We felt the education system didn’t have any time for them, so we set up supplementary schools in order to bring some discipline.’

Kenrick was also part of the British Black Panthers, who fought for the rights of black people and other people of colour.

‘The young generation were critical, to some extent, of the Martin Luther King approach, so we chose something much more direct,’ he says.

‘Rather than asking for mercy, you organise yourself and create some of the resources that you need in order to advance yourself, such as the supplementary schools.’

Kenrick has a degree in economics but forged a career in social work, as social services were keen to utilise his connections with young people in the local area.

He spent the majority of his career working for social services in Brent, in north-west London. He focused mostly on mental health and young people, before taking early retirement in the early 2000s.

Kenrick married Herma in the early 1970s, and they now have three sons and seven grandchildren.

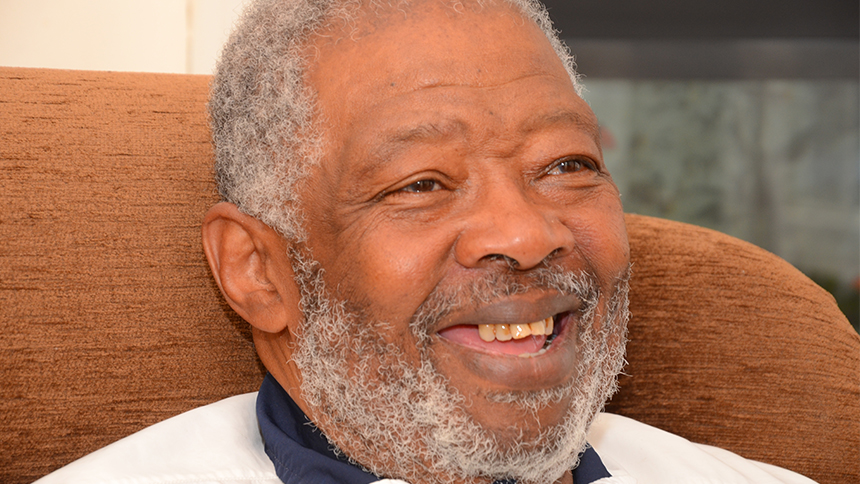

Kenrick is supported by his wife Herma and other family members

Keeping alive

It was in 2014 that Herma first noticed that Kenrick, ordinarily very active and articulate, didn’t seem as mentally sharp as usual. However, she assumed it was just a case of him getting older. Looking back, she feels that her husband became very good at covering up any issues he was having.

Kenrick admits going through a period of denial, and describes the pressure he puts on himself to carry on as normally as possible, to avoid people realising how difficult he might be finding things.

‘Sometimes I recognise the face but I can’t remember the name. Or I remember the name but can’t remember where they came from. How do you explain that to them?’ says Kenrick.

‘Because of how I lived in the community, I’m always having people asking me a question or asking for advice,’ he says.

‘Sometimes I recognise the face but I can’t remember the name. Or I remember the name but can’t remember where they came from. How do you explain that to them?

‘I know my community – don’t tell them “no”, because the first thing they’ll say is, “Now you’ve retired and got a pension you no longer care about us” – they’re sensitive.

‘So if you know that’s going to happen, you’re going to have to try your best.’

Kenrick may explain to people that he has Alzheimer’s, but he says many aren’t able to accept that someone like him could be so badly affected by it.

That said, he still draws positives from these situations.

‘When someone you haven’t spoken to for three or four years phones you up, you’re trying to work out the image of what they were like the last time, which helps to keep me more mentally fluid,’ he says.

‘And even if I can’t help I can sometimes counsel, which is actually quite rewarding.

‘It keeps me involved – actually it keeps me alive.’

Greater anxiety

After his symptoms became impossible to ignore, Kenrick sought medical help and was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in December 2014.

He feels that some older members of the African Caribbean community see dementia in a religious rather than medical context.

‘They’re in a state of denial and don’t want to accept that it is a natural disease,’ he says.

‘They’ll say, “Dementia is because you didn’t go to church, you didn’t say the Lord’s prayer – it is a punishment of God.”

‘But I think it’s opening up. The younger generation is not so much tied to the superstitions of the old.’

‘The image I market is not 100% of what I feel,’ says Kenrick.

Despite coming across as a jovial figure with a broadly positive outlook, Kenrick does admit to having private concerns about his dementia.

‘The image I market is not 100% of what I feel,’ he says.

‘I have a greater anxiety level when I’m quiet, particularly when it dawns on me that I’d planned to do something that then went out of my mind.

‘Herma may mention it casually and I say to her, “By God, it’s gone.”’

Kenrick also has diabetes and has had three stents in his heart as a result of angina.

However it is dementia that worries him most, as he fears it affecting some of his key characteristics.

‘Feeling that I might not be able to express myself in the way or the language that I want because of the anxieties I have – it does shake you up a bit,’ he says.

Kenrick attends weekly groups to keep himself active and involved

Straightforward support

As a result of sepsis, Kenrick now walks with the aid of a frame. He has also stopped driving and his lack of mobility and freedom, along with the dementia, have caused a downturn in his motivation.

His wife and sons do their best to help him remain active and involved, meaning Kenrick is usually out of the house three or four times a week attending various groups. This includes the dementia café run by community resource centre Ashford Place, and two groups at Willesden City Mission.

Kenrick and Herma also attend lectures and concerts, while their grandchildren often visit at weekends.

Kenrick says it’s difficult for his sons to accept that he is declining mentally, and he thinks they can be over-protective at times.

However, he remains grateful for their involvement.

‘There’s supportive indulgent and there’s supportive directive, and I think my family have been much more directive than indulgent,’ he says.

‘They’re straightforward and up front, and that has been beneficial.’

Having always been someone who helped others with their problems, Kenrick has had to acknowledge that he is now the one in need of assistance.

‘You get to a point where you have to accept that you need support – you’re not only a provider of it,’ he says.

Next steps

- Read our Keeping active and involved booklet.